We have built civilizations between us, but we have never been able to build a wall high enough to keep out the dark.

A Darkness You Can Feel

A few weeks ago, we went for a night drive along the shadowy roads near our campus. When I say it’s dark, I mean a darkness so complete it’s difficult for most Americans to imagine. The thick canopy of trees swallows every fragment of ambient light.

In that thickness, I noticed something, something that appeared enormous. A pair of glowing eyes and the outline of a huge antler rack floated among the tree trunks.

Surprisingly, my first thought wasn’t “sambar deer,” though that’s what the creature turned out to be. They roam the roads at dusk and into the night; I’ve seen them plenty of times before. But this time, a chill twisted in my gut, and the word “Wendigo” surfaced in my mind instead.

And this got me thinking. What legends, spirits, and spooks reside in these mountains and forests? Are they too different from the ones I have read about and heard among the Appalachian forests and beyond?

So, this Halloween, let’s wander a little, through the misty mountains and red clay roads of the world, to meet these tales who speak in different languages, but murmur the same human fears.

Let’s meet these tales, one by one…

The Woman Who Walks at Night

In northern India, there is the Churel, a woman wronged in life who returns after death, often seeking vengeance. Her appearance is hideous: backward-facing feet, a black tongue, rough lips, and long, lank hair. But don’t be fooled: she can shapeshift into a beautiful young woman, luring men from lonely roads, then draining them of blood or life. By dawn, her victims are found aged and gray.

Their eternal sorrow becomes a weapon, a force of nature that refuses to be ignored.

If that sounds familiar, it should. Across the world, Mexican and Southwestern communities tell of La Llorona, the “Weeping Woman” who searches for her drowned children by the riverside, calling out to travelers who stray too close. Just hearing La Llorona’s cries means misfortune or death for the unlucky person.

These stories echo the pain of women betrayed and silenced by those who failed them. Their eternal sorrow becomes a weapon, a force of nature that refuses to be ignored.

But the night isn’t the only thing to fear. There are also the hungry…

The Hungry Dead

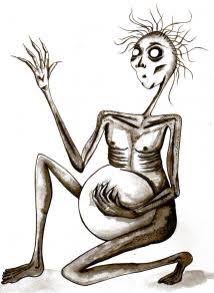

In Buddhist and Hindu belief, there are the Pretas, which are hungry ghosts, cursed with throats too narrow and stomachs too large to ever be filled. They wander unseen among the living, forever searching and eternally unfulfilled.

…when insatiable greed consumes a person, they are transformed into the very monster they once feared.

Half a world away, among Algonquian peoples of North America, there’s the Wendigo, a spirit consumed by hunger, forever craving human flesh. It roams through the deep winter and forests, possessing unsuspecting humans, including the gluttonous and the starving, and turning them into cannibals.

The lesson is the same across seas and continents: when insatiable greed consumes a person, they are transformed into the very monster they once feared. It is a cautionary tale written in the pangs of an empty stomach.

And then there are the monsters born not from hunger, but from desire…

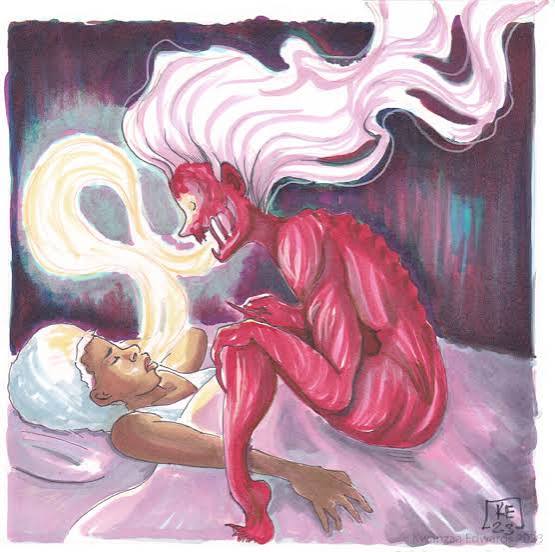

The Lover’s Curse

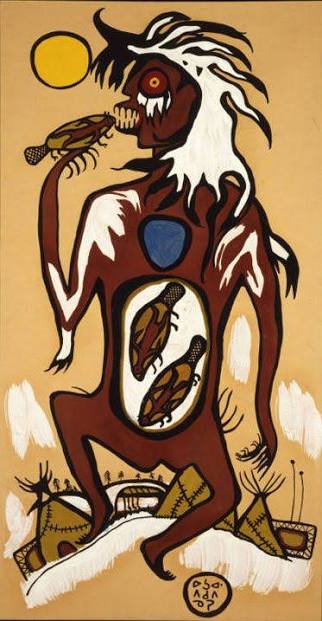

In Kerala, the coastal state at India’s southern tip, they tell of the Yakshi, a beautiful woman with jasmine-scented hair and a smile that hides her true nature. She appears at night under palm trees, asking lonely men for company, then drinks their blood.

…these are women who have been made monstrous through the fears and transgressions of men.

Let’s travel to the American South where they have their own deadly spirits. There’s the Boo Hag of Gullah folklore, who slips into sleeping bodies to ride them through the night, draining the person’s life force and causing them to feel exhausted. And then, we’ll find the Deer Woman, told across many Native American nations (and later found in Appalachian lore), who has dual roles as both protector of women and children and terrorizer of men, luring them to their deaths.

Each is a story where beauty and danger wrap around each other; a lesson (or warning) that desire can be as perilous as fear.

But beneath this surface lies a more ancient, predictable truth: these are women who have been made monstrous through the fears and transgressions of men. They are the reflections of patriarchal anxieties, where female power and sexuality become deadly.

But we don’t always have to travel so far into the past to find things that terrify us…

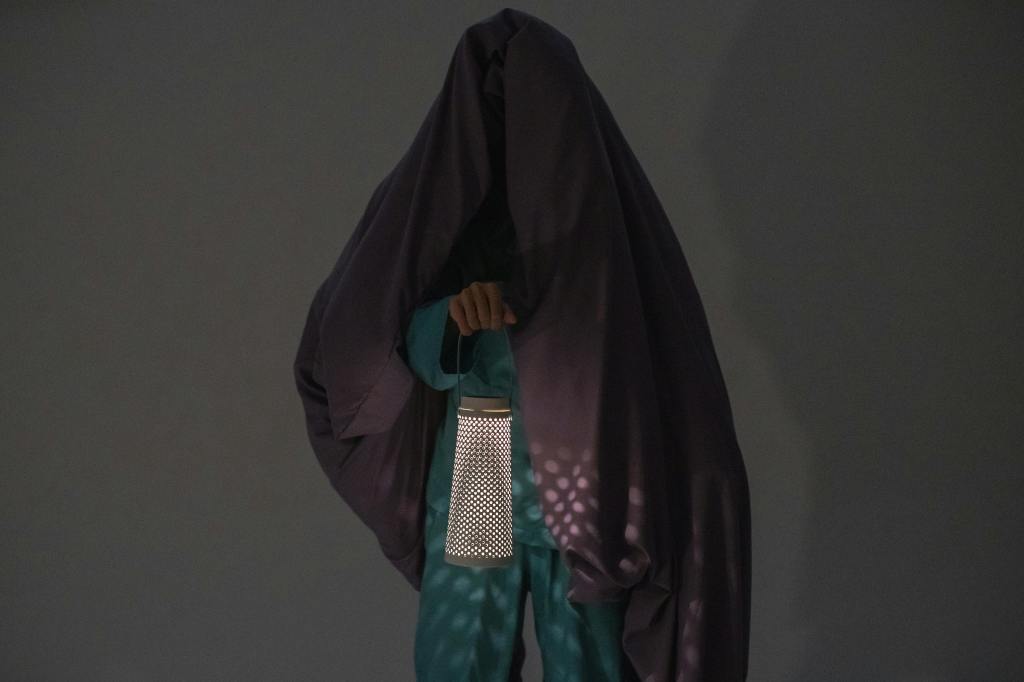

The Ghost Who Knocks

In the 1990s, a strange panic gripped Bangalore, India. People began to say a witch roamed the streets, knocking on doors at night. She could sound like your mother, your friend, anyone you trusted. If an unlucky soul answered the door, they would be found deceased soon after. The only way to keep her out was to write “Nale Ba” (“Come Tomorrow”) on your door.

The ancient fears that haunted our ancestors in the forest have learned to knock on our urban doors.

It’s eerily close to the more modern American legends like Bloody Mary, whispered at sleepovers, or the Mothman who appeared before disasters. Every age invents its own ghost, and the city’s concrete replaces the forest, but the uneasiness stays the same.

The Nale Ba legend is a terrifying reminder that our modern world is a thin facade. The ancient fears that haunted our ancestors in the forest have learned to knock on our urban doors.

But it’s not only spooks and spirits that can scare us. There are beings that can shapeshift into or imitate humans…

The Shapeshifter’s Secret

From the tomes of Hindu mythology is the Ichchhadhari Nagin. It is a serpent that can become a woman, taking human form mostly to seek revenge if her lover is harmed. She is ancient, divine, and deadly.

…this illuminates the fear of crossing lines between human and animal, good and evil.

To the west, in Navajo tradition, tales of Skinwalkers describe witches who take animal form through forbidden ritual. Misrepresented often in pop culture, they remain one of the most secretive and feared figures in Native belief. They are said to also mimic the voice of loved ones and are even able to possess a human.

Both of these spirits terrify through transformation, and this illuminates the fear of crossing lines between human and animal, good and evil. But they’re also stories about identity and justice: who gets to decide what form is “pure,” and what happens when that line is crossed.

The Universal Language of Fear

Ghost stories are rarely just about ghosts. They’re about the things a culture struggles to name: grief, injustice, hunger, desire, guilt.

That’s why Indian and American folklore can look so alike.

When we tell these stories respectfully, we’re recognizing that all people haunt and are haunted. Every culture gives its dead a voice, and every voice has something to teach the living.

So this Halloween, maybe the scariest thing isn’t what goes bump in the night. Maybe it’s realizing how alike we all are when the lights go out.

We have built civilizations between us, but we have never been able to build a wall high enough to keep out the dark. And in that primordial dark, we all tell the same stories to make sense of what we cannot see.