Quick take:

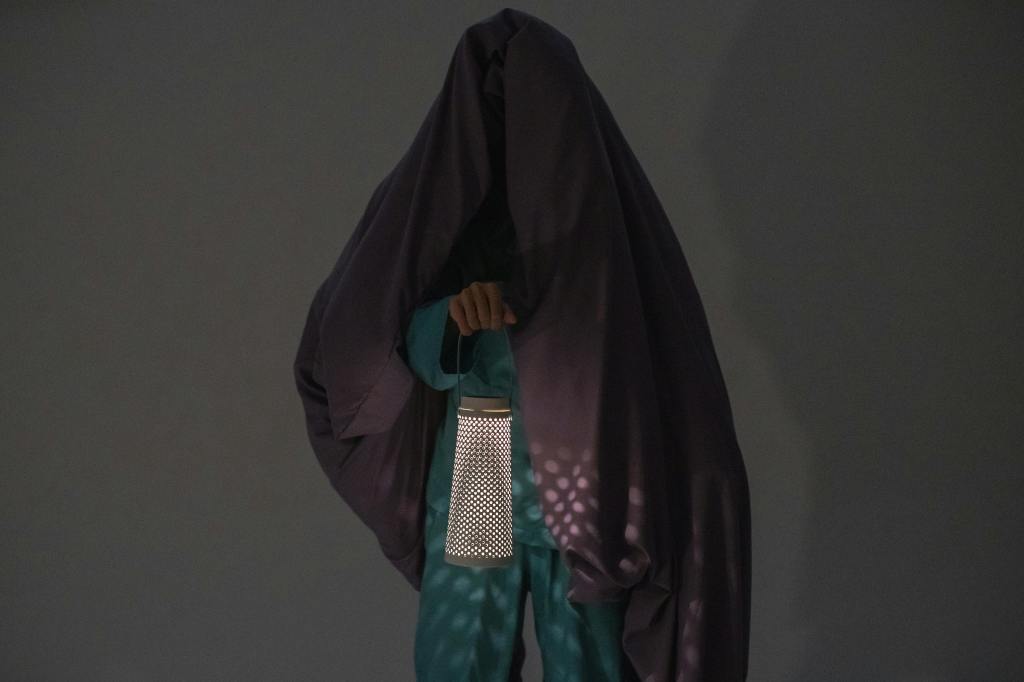

- Heart Lamp is a tender, unflinching collection of stories about Muslim women in Karnataka, mothers, brides, housekeepers, whose quiet lives burn with the fire of the sun.

- The translation avoids italics and footnotes, letting readers step fully into these worlds without exoticizing them.

- Read if you’re drawn to fiction that sits in your heart long after the final page.

Meet Banu Mushtaq

I ordered Banu Mushtaq’s Heart Lamp before I even knew what it was about. On my Facebook feed, I’d come across a post celebrating her Booker Prize win for this collection of short stories. What drew me in was that her stories had been translated from Kannada, a South Indian language rarely seen on global literary stages. And when I read her acceptance speech quote, “No story is ever small,” I was hooked, long before I cracked the spine of the paperback

But I soon learned that before turning to fiction, Mushtaq had worked as an activist and journalist, advocating for the rights of Muslim women in Karnataka and beyond. The stories in Heart Lamp reflect what she witnessed and heard during that time in her career.

Universal Threads

Stitching together the everyday lives of Muslim women, Mushtaq accomplishes her mission: she takes the personal and makes it political. Each selected tale reveals what it means to be a woman, not only within the homes and streets of her stories, but also within the larger currents of a global reality. Though several terms (“jama’at,” “kafan,” “seragu,” “mutawalli,” among others) were unfamiliar to me, Mushtaq writes with such intimacy that definitions feel unnecessary; the emotions of her characters go beyond language.

For example, in “Black Cobras,” much of the action unfolds within the walls of a mosque, with references to Quranic rules I know little about. Yet the desperation of Aashraf, a mother staging a sit-in protest, is visceral:

“The powdery rain falling relentlessly…had not cooled the fire in her gut… The hunger that was gnawing at her stomach with sharp nails had not weakened her…. hers was a dog’s belly that could be filled somehow or the other…. She was ready to fight for [her children’s] right to live their lives.”

This primal urge to protect her children is recognizable to so many mothers.

And in another story, “Be a Woman Once, Oh Lord!,” Mushtaq tackles arranged marriage and dowry harassment with equal force. Yet even for those of us untouched by these realities, she writes lines that pierce with familiarity:

“I was on the road to becoming a mother myself but I stood in a corner constantly looking back down the road to my maternal home.”

Who hasn’t, at some point, longed for the comfort of their mother?

A Big “No” to Italics

Beyond the book’s themes questioning patriarchy and traditions (cultural and religious), something I appreciate about it is translator Deepa Bhasthi’s decision not to italicize non-English words or use footnotes to define transliterated terms. After living in a South Indian state for nearly 13 years, I’m acutely aware of English’s chokehold on the world. A book like this, telling stories and struggles of women that feel universal, would have lost some of its immediacy if italics had pulled my mind out of the narrative. While reading, it didn’t matter whether I knew every Kannada or Islamic term; what I felt was the anguish, the numbness, the power in these tales.

I also agree completely with Bhasthi’s statement: “Italics… announce words as imported from another language, exoticising them and keeping them alien to English.” Now, as I reflect on the book, I can look up the words I didn’t know, gaining something new because of her choice.

Even without definitions and italics, Mushtaq’s prose flows with an intimacy that draws the reader inside the minds of these women, or into the homes of their families. Certain images recur across the collection—the heart as a lamp or a toy, hands pressed to walls, the relentless rain and heat—forming threads that stitch these tales into a mourning shroud.

Though her narratives are rooted in Kannada culture and the lives of Muslim women, they never exclude; instead, they open doors for readers to step into unfamiliar worlds. Much of this accessibility is thanks to Bhasthi’s translation, which preserves the original’s cadence and quirks while letting Mushtaq’s political and social undertones ripple outwards.

There’s a restraint to the storytelling, even in moments of despair or rage, that makes the emotional weight hit harder. Mushtaq never shies from truth or harsh reality either: the women who act on their “big-big” feelings in these stories often come from more privileged social and financial backgrounds. Those without such privilege are often forced to stay mute, for whatever repressive reason, but their silence feels no less powerful.

Kinship and Solidarity

Along with this silence, what lingers most after finishing Heart Lamp is not just the stories themselves but the sense of solidarity that flows from the narratives to the reader. Mushtaq gives voice to women who might never otherwise be heard.

Yaseen Bua, the long-suffering housekeeper in “The Shroud,” is a perfect example. Abandoned by her husband, she cleans and cooks for several families, quietly saving for her one dream: her son’s wedding. But as her body begins to fail, she is struck by the inevitability of her own death. With her meager savings, she makes a single request of her employer: to bring back a burial shroud soaked in ZamZam water from Hajj. By the end of this story, we should be pressing palms to our eyes in shame over the selfishness of the privileged and the self-erasure of the marginalized.

Reading these stories felt like both a revelation and a bridge. As someone far removed from these cultural specifics, I kept returning to the universality of Mushtaq’s characters: their pain, their perseverance, their subdued resistance. I was especially moved by a moment when a bride, after pressing her hennaed hands to the western wall of her new home, is suddenly assaulted by the weight of her new life:

“…her sisters-in-law, brothers-in-law, their expenses, food, clothing, a mother-in-law who was always sick… Her own dreams withered away.”

In these brief moments, Mushtaq delivers on her claim that “No story is ever small,” reminding us how even the quietest lives can burn with the fire of the sun.

The Weight of Womanhood

Mushtaq’s stories resist simplification. For as many unlikable men that are in this book, there are unlikable wives, mothers, and daughters-in-law. The stories are layered with the injustices, compromises, and overall oppression that women endure daily.

Even though many of these stories were written in the early 1990s, they remain painfully relevant today, as seen by the endless stream of tragic headlines. As the final story reminds us, the experience of womanhood cannot be understood from a distance. “Come to earth as a woman… Be a woman once, Oh Lord!”

Note: Images sourced from Pexels.